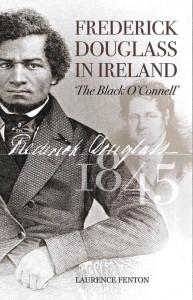

Review of Frederick Douglass in Ireland by Laurence Fenton, published by the Collins Press

Published in Books Ireland Magazine, July/August 2014

Rarely have the life and exploits of a person who lived in the nineteenth century and visited Ireland for only a few months received such exposure in so short a period of time. The first time I heard of Frederick Douglass and his 1845 Irish tour was during President Obama’s visit to Ireland in 2011. It is surely no coincidence that Douglass’s visit is also the feature of the first chapter of Colum McCann’s brilliant latest novel Transatlantic and is now the subject of this book. No doubt the recent success of Steve McQueen’s film Twelve Years a Slave, although about another African-American’s experience, has added to the interest.

For those who do not yet know Douglass, Fenton gives a very good introduction to the man. Douglass’s father was probably his mother’s owner—he was fairer-skinned than his siblings—and he was scarred by the death of his mother at the age of six. His life experiences mirrored that of many slaves of the time, but Douglass was fortunate enough to have been shown kindness, which saved him from the worst rigours of the life of a slave on a plantation in America.

Crucially, his circumstances allowed him to learn to read. Interestingly, one of the first texts that he used to teach himself was a 1795 speech by Arthur O’Connor, a United Irishman, made in the Irish House of Commons, which Douglass described as ‘a bold and powerful denunciation of oppression’.

He was regularly whipped by one of his owners until at the age of sixteen Douglass finally grappled with his tormentor. When he had physically subdued him and became, in his own words, ‘A MAN NOW’, he was never whipped again. At the age of twenty he was permitted to hire himself out, with his owner receiving a fee for his services. At that stage he lived a life of relative freedom compared to most slaves. It was after this that he escaped north and found true freedom. There he began his campaign for the end of the subjugation of one human by another.

No doubt much of this very interesting background material is gleaned from Douglass’s account of his life in servitude, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. In fact, it was the occasion of the publication of that book that prompted Douglass on his transatlantic journey. It was felt that, given the furore its publication would cause in America, it would be best for him to undertake a tour of Ireland and Britain, largely at the invitation of members of the Quaker community.

The bulk of Fenton’s book deals with the four and a half months that Douglass spent in Ireland in 1845. He was almost universally warmly received throughout Ireland and during this visit made around 40 anti-slavery speeches, replete with horrific stories of slavery and condemnations of those who supported it. Fenton outlines the embarrassment that Douglass caused particularly to Methodists and Presbyterians over their American brethren’s involvement in and justification of slavery.

Despite the title of the book and the admiration that O’Connell and Douglass had for one another, their one encounter in Ireland—at an O’Connell rally in Dublin—was brief. Douglass was transfixed by O’Connell and he was brought on stage to address the crowd. And there the episode curiously ends.

Fenton includes some relatively long asides into the history of the Quakers, the Corn Laws and the onset of the Great Famine. He also makes some interesting observations, such as the assertion that at the time there was a larger black population in Dublin than in perhaps any other city in Europe outside of London, and that the women of Ireland fawned over Douglass.

Fenton gives detailed accounts of each of the places that Douglass visited—Dublin, Wexford, Waterford, Cork, Limerick and Belfast. There were full houses, rave reviews and thousands of copies of the Narrative sold. There is also mention of the behind-the-scenes tensions that developed between the visitor and his hosts, but a drawback of the book is the lack of detail about and insight into this aspect. Presumably Fenton’s account is based on as much information as is available. Owing to the unavoidable lack of discrimination, however, an insufficient portion is of the ‘telling’ variety.

It is probably for the same reason that the conclusions at the end of the book feel a little empty. Douglass’s visit to Ireland was to have a lasting impact on him and his subsequent career (which included advising President Lincoln). On leaving Ireland, he stated that because of his experiences there he had undergone a transformation—‘I live a new life’, he wrote.

His world horizons had expanded considerably beyond the issue of slavery, and the acceptance he received in Ireland no doubt boosted his confidence, though he never lacked for that previously. It is a pity that this is not documented during the Irish section of the book—presumably because Douglass did not write then about the timing or nature of his moments of epiphany.

Despite any shortcomings, this nevertheless is a well-written and researched book that gives an interesting insight into a man and his relationship with Ireland.